Futures Rise Ahead Of Critical Nvidia Earnings

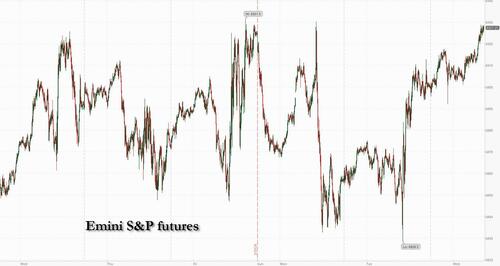

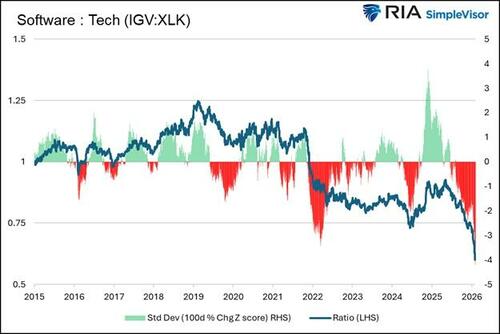

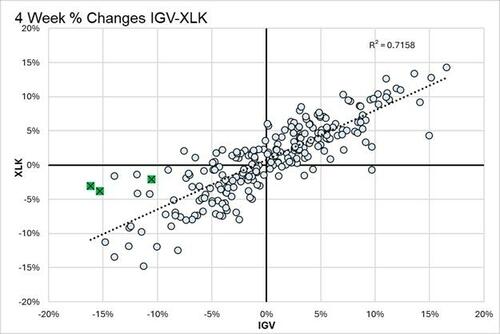

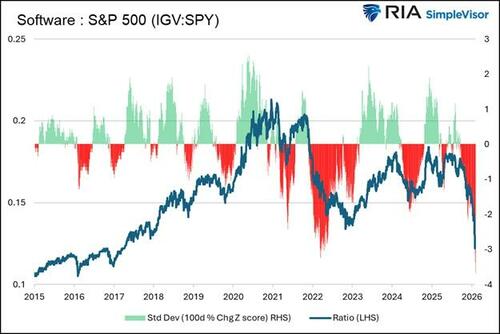

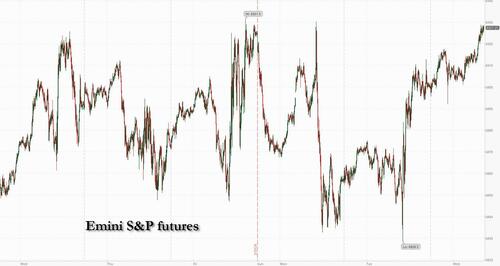

US equity futures are higher into NVDA earnings release after the close, and the risk-on tone in the US yesterday has spread globally with tech giant's earnings a catalyst for maintaining the rally aided by Tech. As of 8:00am ET, S&P 500 futures were up 0.3% as with Nasdaq 100 contracts +0.4%; NVDA is up 0.6% in premarket trading and while blowout results from the company later today may soothe nerves about the AI trade, “even if they have tremendous numbers, we know the markets are really fickle,” said Mahoney Asset Management’s Ken Mahoney. Other Mag7s are also higher ex-AAPL and TSLA with Cyclicals bid, led by Fins/Industrials/Materials while Defensives mostly lower pre-mkt, ex-Healthcare, reflecting the risk-on tone. JPM says to keep an eye on Software if TMT gains positive momentum. European stocks rose 0.5%, hitting a record on a rebound in banks and miners. South Korea pushed past France in stock-market value.Bond yields are +1-3bp, the dollar slipped after President Donald Trump doubled down on his commitment to tariffs, before erasing the move, and commodities are bid led by Metals with precious outperforming base especially silver and platinum. Bitcoin rallied more than 2%. Gold and silver climbed. Today’s macro data releases are light (only Mortgage Applicatgions which rose 0.4%) ahead of tomorrow's jobless claims and Friday’s PPI, but with multiple Fedspeakers. Yesterday we saw better weekly ADP data, weaker regional Fed data, and improving consumer sentiment.

In premarket trading, Magnificent Seven stocks are mostly higher, with Nvidia +0.8% ahead of its report (Alphabet +0.5%, Amazon +0.5%, Microsoft +0.3%, Meta Platforms +0.3%, Tesla +0.4%, Apple -0.2%).

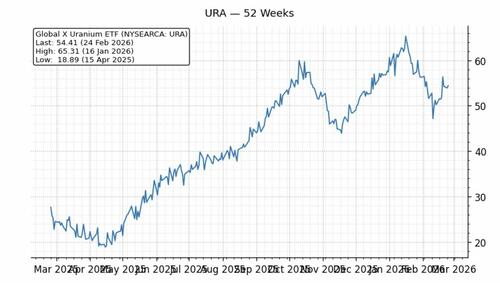

- Lithium stocks are rising after Zimbabwe suspended exports of lithium concentrates and raw minerals.

- AbCellera Biologics (ABCL) rises 8% after the drug developer reported total revenue for the fourth quarter that was ahead of the average analyst estimate. The firm also posted loss per share for the quarter that was narrower than Wall Street’s expectations.

- Aspen Aerogels (ASPN) falls 21% after the maker of thermal insulation used in electric vehicles reported loss per share for the fourth quarter that’s wider than expected. The company has initiated a strategic review.

- Axon (AXON) rises 15% after the Taser maker reported adjusted earnings per share for the fourth quarter that beat the average analyst estimate.

- Camping World (CWH) slides 12% after the retailer of recreational vehicles reported a larger-than-expected adjusted Ebitda loss for the fourth quarter.

- Cava Group (CAVA) climbs 11% after the fast-casual chain’s restaurant comp sales forecast for 2026 came in above the average estimate from analysts.

- Circle Internet Group Inc. (CRCL) rises 16% as profit and revenue increased more than estimated while the amount of its USDC stablecoin in circulation jumped 72% to $75.3 billion in the fourth quarter.

- First Solar (FSLR) slides 16% after the maker of electricity-producing solar modules reported a 2026 net sales forecast which missed the average analyst estimate.

- HP Inc. (HPQ) falls 5% after providing a profit outlook for the current quarter that may fall short of estimates and said full-year earnings will likely hit the lower end of a previously forecast range as the company copes with tariffs and the rising price of memory chips.

- Lowe’s Cos. (LOW) slips 3% after forecasting sales guidance for the full year that fell short of expectations, a sign the housing market will remain lackluster in the near term due to high borrowing costs and economic volatility.

- Lucid (LCID) declines 2% after the electric-vehicle maker reported adjusted loss per share for the fourth quarter that missed the average analyst estimate.

- MercadoLibre (MELI) falls 5% after the online marketplace for Latin America reported its fourth-quarter results. While analysts are broadly positive on growth trends, they noted that elevated spending will pressure the company’s margins.

- Oddity Tech (ODD) slumps 34% after the direct-to-consumer beauty and wellness company said it expects its revenue for the first quarter of 2026 to decline 30% year-over-year.

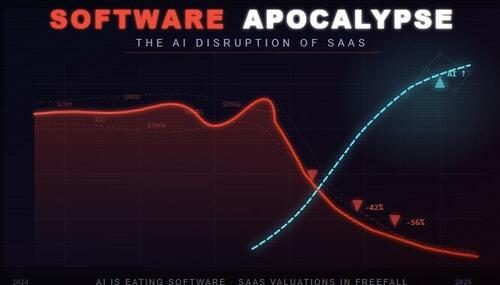

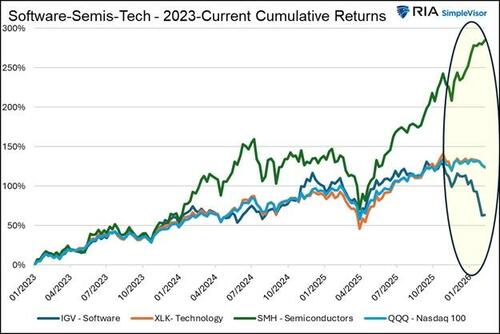

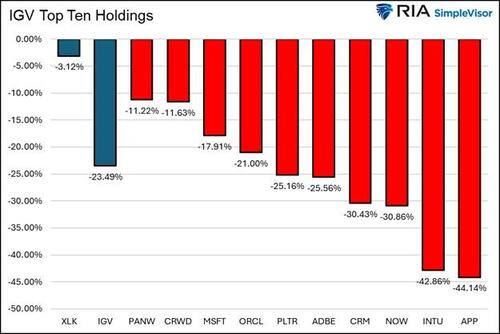

- Workday (WDAY) declines 9% after giving a subscription revenue guidance that missed expectations, adding to investor concerns that a rise of AI automation tools is disrupting traditional software vendors.

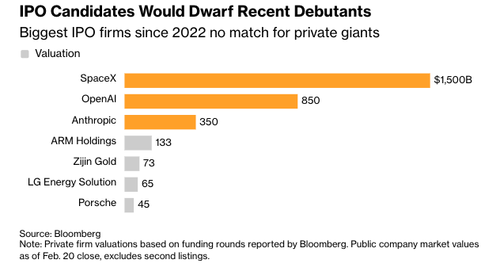

In other corporate news, DoorDash is pulling out of four countries in Asia, a sign that fierce competition and thin margins are weighing on its overseas ambitions. Anthropic has loosened its central safety policy, coinciding with a growing dispute with the Defense Department. AMC plans to close more theaters in underperforming locations.

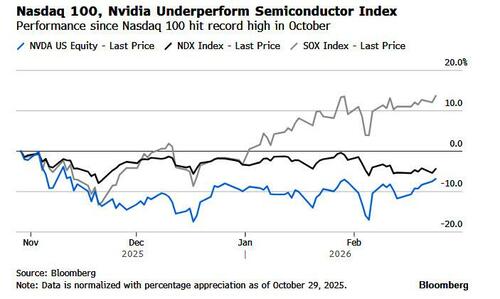

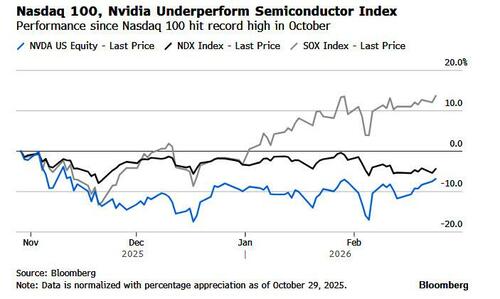

Expectations are high for Nvidia as customers have announced huge capex plans, but a positive stock reaction is key for the Nasdaq after recent underperformance, said Arnaud Girod, head of cross-asset strategy at Kepler Cheuvreux. “We’re in the thick of uncertainty about the disruption of AI with the market de-rating entire segments of the stock market.”

To reinvigorate its stock performance, Nvidia will at least need to beat its prior outlook and set new targets above current Wall Street estimates. While the company has done this repeatedly, concerns have grown that the AI spending wave isn’t sustainable. “Nvidia’s results are expected to be good given the massive capex announced by its clients, but it’s all about how the market will react,” said Arnaud Girod, head of cross-asset strategy at Kepler Cheuvreux. “The Nasdaq needs Nvidia if it is to limit its current underperformance.”

Another key earnings event on Wednesday is Salesforce, the cloud-based customer-relationship firm whose stock has plunged 30% this year after getting caught up in the selloff of software companies on fears that AI could render their services obsolete. Analysts, on average, project that the company will post its best quarterly revenue growth rate in three years. Still, highlighting the risks for software-as-a-service firms, Workday Inc. slid nearly 10% in early trading after subscription sales fell short of estimates.

Turning to Trump's State of the Union address, the President talked up the economy saying that the nation is back, bigger, better and stronger than before, while he added that we've seen nothing yet and this is the golden age of America.

- Trump said they have achieved a transformation like never before and a turnaround for the ages, as well as stated that low interest rates will solve the housing problem, and they want to protect home values and keep them up.

- He also commented that inflation is plummeting, salaries are rising, and the roaring economy is roaring like never before.

- Regarding tariffs, Trump said the Supreme Court decision on tariffs is very unfortunate, but added that tariffs will remain in place and nearly all countries want to keep the trade deals, while he also stated that congressional action won't be needed on tariffs.

- Trump also commented on Iran, which he claimed is working on missiles that could soon reach the US, and noted Iran wants to make a deal but hasn't yet said that it won't pursue nuclear weapons, while he reiterated that his preference is to resolve Iran's nuclear issue through diplomacy.

Out of the 450 S&P 500 companies that have reported so far in the earnings season, 74% have managed to beat analyst forecasts, while 21% have missed. TJX, Bank of Montreal and Lowe’s are among companies expected to report results before the market opens. Wall Street expects TJX’s fourth-quarter results to have received a boost from a strong holiday shopping season, with comparable sales estimate of +3.7% (Bloomberg Consensus). Earnings from Nvidia and Salesforce follow later with Wall Street eager to hear what it has to say about potential disruption to software makers from AI upstarts like Anthropic.

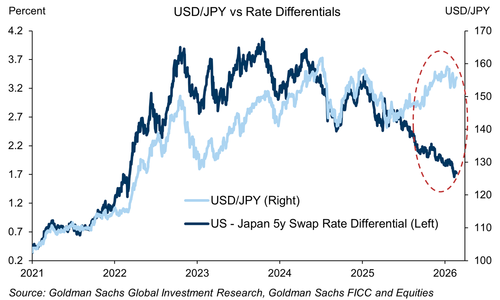

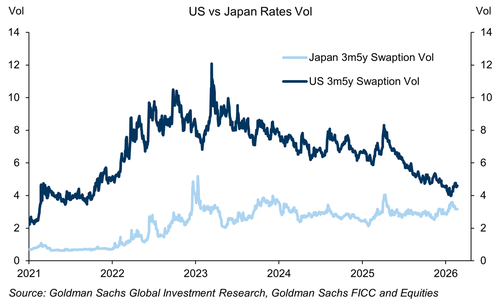

Rates on Japan’s longer-term bonds climbed further after Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s government nominated two new Bank of Japan policy board members who are seen as dovish. The yen fell 0.5%, the worst performance among major currencies.

European stocks are higher across the board with the FTSE 100 outpacing peers as post-earnings gains in HSBC send the index to a record high. Mining and banking shares are leading gains. Meanwhile, food and beverage as well as personal care stocks are the biggest laggards. Here are the biggest movers Wednesday:

- HSBC shares advanced as much as 6.1% in London to a fresh high after the lender reported strong earnings ahead of estimates and offered new guidance figures that analysts say are above expectations

- Relx shares rise as much as 5.3% after the professional publisher says it’s integrating an Anthropic automation tool into its legal research platform

- Anglo American rallied as much as 4.4% in London after DZ Bank upgraded the miner to buy from hold, saying that the merger with Teck Resources to become one of the world’s biggest copper producers is going as planned

- Lion Finance Group shares climb as much as 9.8% to the highest level on record, after the Georgian lender reported strong fourth-quarter results

- Temenos shares rise as much as 8.6%, the most since October, after the software firm raised its mid-term targets for annual recurring revenue, free cash flow and Ebit, while issuing fiscal 2026 guidance that met expectations

- St James’s Place shares climb as much as 7.3%, the most since July, after the British wealth manager reported underlying cash profit for the full year that beat the average analyst estimate

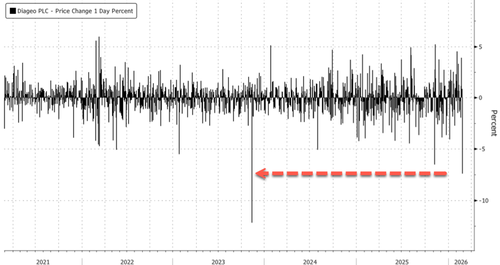

- Diageo shares fall as much as 7.1% after the maker of Guinness stout and Johnnie Walker whiskey cut its sales guidance due to further weakness in the key US market, and reduced its dividend

- Haleon shares drop as much as 5.6% after the consumer healthcare firm delivered weaker-than-expected organic growth in the final quarter of 2025 and issued guidance that was below its mid-term ambition

- Iberdrola shares slip as much as 1.5%, ceding earlier gains, after the Spanish power company’s fourth-quarter net income missed estimates, overshadowing a 12% rise in full-year 2025 results

Earlier in the session, Asian stocks rise for a third straight day, led by tech stocks, as investors pared concerns over potential disruption from artificial intelligence. The MSCI Asia Pacific Index gained 1.1% at the close to remain near record highs, with chipmakers TSMC and Samsung continuing to drive advances. Benchmarks in Japan and Taiwan rose more than 2%, while Australian and Korean shares also gained over 1%. Asia’s equity markets have avoided some of the volatility sweeping Wall Street in recent weeks, as investors remain confident about the region’s role in supplying essential AI components to the US. On Wednesday, the region’s tech firms were further supported by comments from Anthropic PBC that it plans to build partnerships with existing businesses.

“Today’s firmer Asia open, following the US rebound, looks like a reset from oversold levels,” said Ritesh Ganeriwal, head of investment at Syfe Pte in Singapore. “The bounce in US tech is providing near-term relief to sentiment.” “That said, we would characterize this as tactical stabilization rather than a full reset of positioning. Markets are still digesting valuation, earnings visibility, and AI monetization assumptions.”

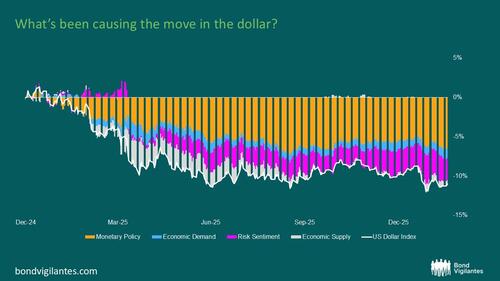

In FX, the Bloomberg Dollar Spot index is now up a touch as yen weakness helped the greenback shrug off initial downside. The yen was sold and the JGB curve steepened after Japanese PM Takaichi nominated two dovish reflationist academics to join the BOJ board.

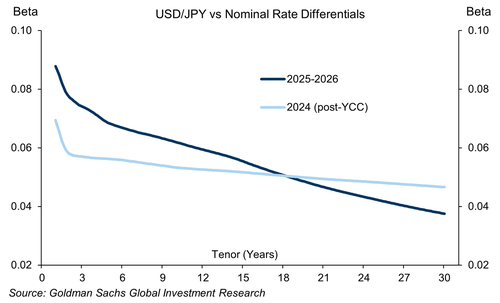

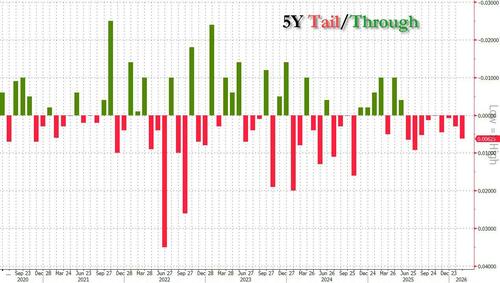

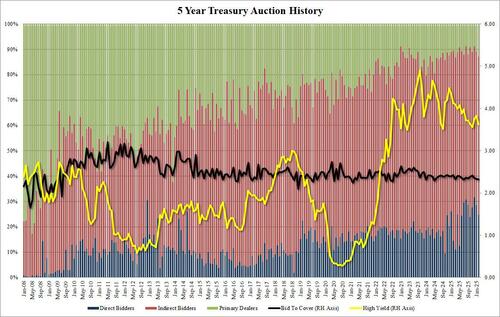

In rates, treasuries are slightly cheaper in early US trading as stock futures advance and investors set up for 5-year note auction at 1pm New York time.US yields are 1bp-3bp higher and curve spreads are within 1bp of Tuesday’s close. 10-year near 4.05% is 2bp cheaper, lagging German counterpart by around 1bp.$70 billion 5-year note auction follows solid results for Tuesday’s 2-year; WI 5-year yield near 3.618% is ~20.5bp richer than last month’s auction, which tailed by 0.3bp. Elsewhere in the rates space, US yields are up 1-2bps across the curve with modest upside also seen in German and UK borrowing costs.

While Treasuries showcased their haven status during Monday’s tech selloff, longer-term pressures including uncertainty over inflation, tariffs and fiscal questions remain, according to Laura Cooper, head of macro credit at Nuveen. “We are unlikely to see the resumption of rate cuts until we see greater signs of disinflationary pressures coming through, which to our mind is more of a second-half-of-2026 story,” Cooper told Bloomberg TV. “All of the factors suggest we are in a higher-for-longer yield backdrop.”

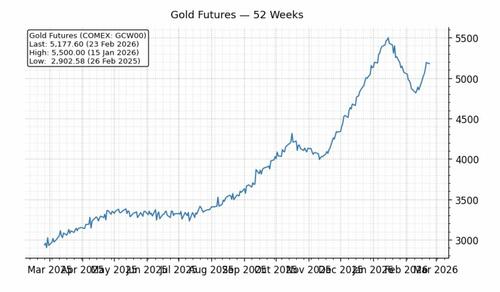

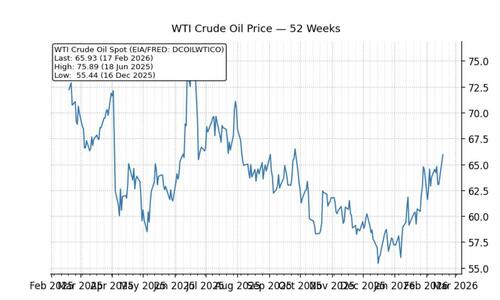

In commodities, WTI crude is up 0.3%, but down from highs. US President Donald Trump stated that Iran is working to reconstitute its nuclear program. Spot gold and silver are up 0.5% and 3.5% respectively. Bitcoin is up 2.1% after a recent run of losses.

The US economic data calendar is blank, while Fed speaker slate includes Barkin (10:40am), Schmid (11am) and Musalem (1:20pm)

Market Snapshot

- S&P 500 mini +0.1%

- Nasdaq 100 mini +0.2%

- Russell 2000 mini +0.4%

- Stoxx Europe 600 +0.6%

- DAX +0.4%

- CAC 40 +0.4%

- 10-year Treasury yield +2 basis points at 4.05%

- VIX little changed at 19.51

- Bloomberg Dollar Index little changed at 1189.37

- euro +0.1% at $1.1786

- WTI crude +0.4% at $65.89/barrel

Top Overnight News

- Donald Trump accused Iran of reviving its nuclear program in his State of the Union address, adding to speculation of new US strikes. BBG

- Trump pledged a new retirement savings plan for workers without 401(k)s. It would be modeled after the federal Thrift Savings Plan, with a government match of up to $1,000 annually. BBG

- US House Speaker Johnson said codifying some of the tariffs would be difficult and will have discussions on tariffs in coming weeks, via Fox Business Interview.

- The Pentagon threatened to invoke a Cold War-era law against Anthropic unless it allows unrestricted military use of its technology by Friday, people familiar said. Anthropic said in a blog post that it’s loosening its hallmark safety pledge.

- Nvidia Corp. has yet to sell any of its H200 chips to China two months after President Donald Trump’s decision to allow shipments of the artificial intelligence processors to the world’s second-largest economy. BBG

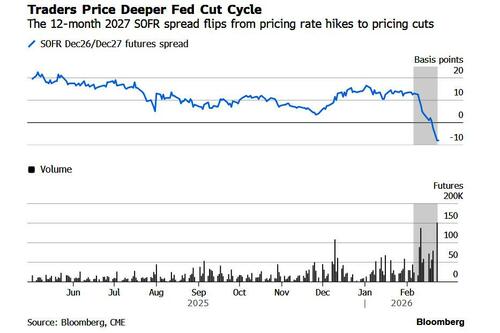

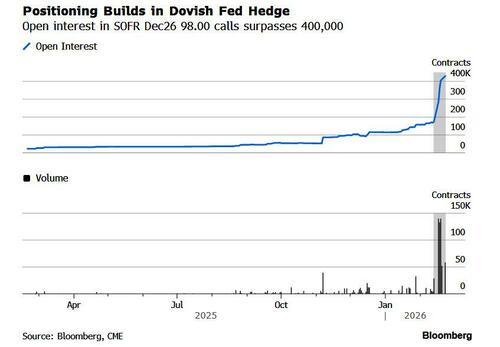

- Two Federal Reserve officials on Tuesday signaled no near-term appetite to change the setting of central bank interest rate policy. Markets expect the Fed to lower rates again this year but officials, faced with a stabilizing job market and uncertainty over whether inflation pressures will moderate back to target, have not given much guidance about the prospect for more reductions in the cost of short-term borrowing. RTRS

- Japan must keep raising interest rates and tighten fiscal policy as the economy is already in "great shape," former central bank chief Haruhiko Kuroda said, warning that Premier Sanae Takaichi's big spending plan could stoke an inflationary upswing. RTRS

- Japan’s government has nominated candidates for two positions at the central bank, a move that could be viewed as a chance to influence monetary policy in a more dovish direction. WSJ

- The Aussie gained as January core inflation came in stronger than expected. The Bank of Thailand unexpectedly cut rates to 1%. BBG

- Consumers expecting a drop in prices after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the White House's emergency tariffs are likely to be disappointed, as businesses plan to use any relief to offset elevated costs and gird themselves to chase refunds. RTRS

Trade/Tariffs

- China's Commerce Ministry, on USTR Greer comments, said that China has fulfilled obligations of China-US phase one agreement.

- China's Commerce Ministry announces that the country encourages imports of services related to chip research, development and design.

- Chinese Premier Li said in meeting with German Chancellor Merz that China is willing to bolster dialogue, communication and mutual trust.

- German Chancellor Merz on trade with China said, they welcome any further market opening and it is in their mutual interest.

- US President Trump said Supreme Court decision on tariffs is very unfortunate, but adds that tariffs will remain in place and nearly all countries want to keep the trade deals, also said congressional action won't be needed on tariffs.

A more detailed look at global markets courtesy of Newsquawk

APAC stocks traded higher as the region took impetus from the rebound on Wall Street after Anthropic's presentation helped soothe some AI/software concerns, and with tech also bolstered by the USD 60bln Meta-AMD chip deal. ASX 200 advanced with gains led by notable outperformance in the tech, consumer staples and mining sectors, while participants continue to digest an overload of earnings and are unfazed by firmer-than-expected CPI data. Nikkei 225 rallied to a fresh record high as exporters benefitted from recent currency weakness after it was reported that Japanese PM Takaichi relayed to BoJ Governor Ueda her reservations about further rate hikes. Hang Seng and Shanghai Comp conformed to the broad upbeat risk sentiment, with attention in Hong Kong on the annual budget and with the mainland underpinned with the PBoC conducting a CNY 600bln MLF operation.

Top Asian News

- China aims to boost output of relatively advanced chips to 100,000 wafers in 1-2 years, according to Nikkei; China has set target of adding an additional 500,000 wafers of capacity by 2030.

- Shanghai City relaxes home buying rules for non-residents effective on Thursday and will exempt property tax for certain home buyers.

- Japanese PM Takaichi said closely watching FX moves with a high sense of urgency.

- Major Japanese brokerage warns that yen could test post-election low if BoJ appointments are dovish.

- Hong Kong Financial Secretary Chan said in Budget Address that 2025 GDP rose 3.5% and the domestic economic trend is to continue to be good in 2026. Sees 2026 GDP at 2.5%-3.5% and average growth of 3.0% per year in real terms for 2027-2030.

- Hong Kong budget is speculated to include funding for tech hub and aerospace sector incentives, according to SCMP.

European bourses (STOXX 600 +0.6%) are entirely in the green, with the FTSE MIB and FTSE 100 (+0.9%) gaining, helped by positive HSBC earnings. The SMI (+0.1%) is the slight laggard, weighed down by Alcon (-1.1%) after the Co. missed on Q4 revenue and core EPS. European sectors are broadly in the green. Banks (+1.8%) and Basic Resources (+2.2%) sit comfortably at the top of the table, while Food, Beverages and Tobacco (-0.7%) is soft as poor Diageo guidance hits the rest of the sector (Pernod Ricard -2.9%, Heineken -0.3%). HSBC shares (+5.5%) are higher today for three reasons: 1) beating market estimates for its top line metrics, 2) lifting its annual 2026-28 ROTE to 17% or greater, and 3) stating its USD 1.5bln cost-saving target will be hit ahead of schedule. This, alongside an update from Santander (+2.7%), in which they expect 2028 net income at EUR 20bln (exp. EUR 18.6bln), lifts the Banking sector.

Top European News

- UK Chancellor Reeves is facing renewed called to cut bank tax as UK competitiveness lags, according to City AM.

- German lawmakers are reportedly set to approve EUR 540mln order for attack drones, Bloomberg reported citing sources.

FX

- DXY trade flat intraday and off worst levels within a current 97.643-97.867 range after briefly dipping under yesterday's 97.695 low, with little reaction to US President Trump's State of the Union Address, where he defended his leadership and described the past year as a “turnaround for the ages”; he promoted tariffs as strengthening the US economy, and said they would “substantially replace” income taxes; he offered limited details on Iran, China and Ukraine. Aside from that, newsflow this morning has been on the lighter side. Focus ahead will be on Fed speak and then NVIDIA earnings.

- JPY underperforms with recent developments seeing PM Takaichi nominating academics Ayano Sato and Toichiro Asada to the BoJ policy board, replacing Asahi Noguchi and Junko Nakagawa; analysts said the picks are viewed as reflationist and dovish, and may reduce expectations of near-term rate hikes. Further, JPY weakness coincided with reports that Japan's FTC conducted an on-site inspection of Microsoft (MSFT) on suspicion of violating the Antimonopoly Act, Nikkei reported, potentially stoking some Big Tech-related bilateral tensions. USD/JPY resides in a 155.34-156.64 range after topping Tuesday's 156.28 high.

- AUD is the G10 outperformer following firmer-than-expected monthly CPI data from Australia. The upside in consumer inflation was driven by electricity and garments & footwear offset somewhat by a larger than expected fall in holiday travel and a smaller than expected rise in health. Analysts at Westpac note "Consistent with our preliminary review we see little risk to our current inflation profile." AUD/USD resides closer to the top end of a 0.7057-0.7117 range at the time of writing.

- GBP and EUR trade with mild gains despite a flat DXY, possibly more a function of JPY weakness as GBP/JPY hovers around 211.50 and EUR/JPY meanders around 184.50. Aside from that, specifics for GBP and EUR are light, with the latter eyeing EZ final inflation metrics.

Central Banks

- Former BoJ Governor Kuroda said Japan need to move toward tighter fiscal and monetary policy as the economy is already in great shape. Recent USD/JPY levels near 157 is somewhat too weak. BoJ can probably hike rates around twice a year in 2026 and 2027 to around 1.5-1.75%. PM Takaichi's administration spending and tax-cut plans could fuel inflation and push up bond yields.

- Japan nominates professors Toichiro Asada and Ayano Sato to replace outgoing BoJ board members Noguchi and Nakagawa.

- Japanese Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary said aware of report that PM Takaichi voiced apprehension to additional BoJ rate hikes, adds Takaichi did not have a specific request and there is 'nothing more or less than that'.

- RBA Governor Bullock said patience is required in assessing policy.

- China may see lower rates from Q2, according to experts cited by China Securities Journal.

- Thai Central Bank unexpectedly cuts its rate by 25bps to 1.00% (exp. a hold at 1.25%); 4-2 voted in favour of the cut; said downside risks to headline inflation are expected to increase relative to previous assessment.

Fixed Income

- Global benchmarks are broadly lower this morning. Pressure which also comes alongside JGB selling, which are currently lower by around 50 ticks. The situation is Japan appears to be shifting from optimism surrounding political stability, after PM Takaichi’s landslide victory, to one where traders are questioning “reflationist” policy; this refers to government’s ability to boost spending whilst also allowing inflation to run higher. Fears which were sparked by reports on Tuesday, that PM Takaichi expressed her apprehension to further BoJ hikes. Moreover, overnight it was reported that the government had recommended two academics, who have been described as “staunch reflationists”, by Chief Fixed Income strategist SBI Securities.

- USTs are lower by a handful of ticks and currently hold within a 113-05+ to 113-10+ range, with price action ultimately sideways for much of the morning. Pressure this morning in tandem with easing AI disruption related fears, after Anthropic announced a slew of new partnerships. Overnight, markets tuned into President Trump’s State of the Union Address, in which he largely talked up the US economy; on trade, he suggested that tariffs will remain in place and nearly all countries want to keep the trade deals. On the Iran situation, he suggested that Iran wants to make a deal, and reiterated his own preference to solve the situation through diplomacy. Overall, his comments did not spur a reaction in US paper.

- Bunds initially held around the unchanged mark early doors, before slipping slightly into the red; currently off by around 10 ticks, to hold within a 129.50-129.71 range. Earlier, Final German GDP (Q4) figures were unrevised, whilst the GfK Consumer Confidence metrics deteriorated from the prior vs expectations of a slight improvement. Little move to the release of Final EZ HICP metrics.

- Gilts follow peers lower, and currently lower by 10 ticks within a 92.94-92.84 range. Focus on Tuesday was on the BoE, where several MPC members appeared at the TSC hearing. Governor Bailey noted that would go into coming meetings asking if a cut is justified, adding that a rate cut at the next meeting is a genuinely open question. Market pricing was little moved following the hearing and are still yet to definitively determine if the next cut will be in March or April. Elsewhere, CityAM reported that UK Chancellor Reeves is facing renewed calls to cut the bank tax as UK competitiveness lags.

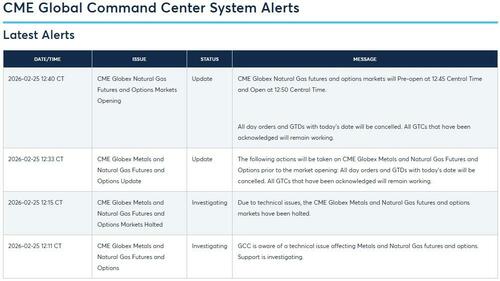

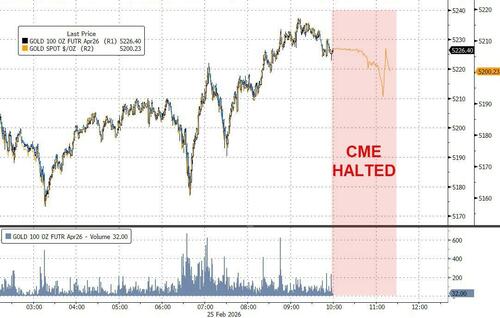

Commodities

- Crude benchmarks remain underpinned, with WTI and Brent trading within the ranges of USD 65.45-66.60/bbl and USD 70.45-71.60/bbl, respectively. Ongoing geopolitical tension between the US and Iran will likely keep oil prices volatile in the near term. At the time of writing, the latest update includes US Senator Cruz suggesting that they are likely to see limited strikes on Iran in a matter of days. Meanwhile, Iranian Foreign Minister Araghchi said Tehran will resume talks with the US in Geneva tomorrow. In Russia and Ukraine, Washington warned Ukraine not to strike targets within Russia that could hit US economic interests, according to the FT.

- In the precious metal space, XAU and XAG continue to surge, trading at the upper range of USD 5128.3-5310.7/oz and USD 86.22-87.10/oz, respectively. The yellow metal has been underpinned by recent dollar softness as well as continuous haven demand over geopolitical uncertainty between the US and Iran.

- Copper prices are slightly firmer this morning, tracking global risk sentiment from Wall Street and APAC, which finished higher, as well as the European session, which is trading mostly positive thus far this morning. At the time of writing, 3M LME copper is trading at the upper end of a USD 13.19-13.29k range.

- Russia and Iran are cutting its oil prices to China, Bloomberg reported citing traders; Russia's Urals grade is selling USD 12/bbl below ICE Brent (prev. USD 10/bbl below), Iranian Light selling USD 11/bbl below ICE Brent (prev. USD 8-9/bbl).

Geopolitics: Ukraine

- Ukraine President Zelensky's negotiators will meet with US counterparts on Thursday and is targeting a leaders summit in March.

- Washington warns Ukraine over striking US economic interests in Russia, FT reported. Kyiv’s ambassador to Washington said the Trump admin has formally warned Ukraine not to strike targets within Russia that could hit US economic interests.

Geopolitics: Middle East

- US President Trump said Iran is working on missiles that could soon reach the US, and noted Iran wants to make a deal but hasn't yet said that it won't pursue nuclear weapons, reiterates his preference is to resolve Iran nuclear issue via diplomacy.

- Iran's Parliamentary Speaker said, with relation to US-Iran talks, all options are on the table. Ready for dignified diplomacy, also ready for defence.

US Event Calendar

- 7:00 am: United States Feb 20 MBA Mortgage Applications, prior 2.8%

- 10:40 am: United States Fed’s Barkin Speaks on Panel

- 11:00 am: United States Fed’s Schmid Speaks on Monetary Policy and the Economy

- 1:20 pm: United States Fed’s Musalem Speaks on Role of Fed

DB's Jim Reid concludes the overnight wrap

Markets recovered their poise over the last 24 hours, with the S&P 500 (+0.77%) advancing thanks to positive US data and a rebound in software stocks. Clearly that mood could change with Nvidia’s results after tonight’s close, but the news led to a bit more confidence in the near-term outlook, and the financial stress at the start of the week eased across several asset classes. Moreover, inflation concerns also fell back after Brent crude oil prices (-1.01%) declined for a second day. So there was a much more positive tone relative to Monday’s selloff, and futures on the S&P 500 (+0.01%) are just about higher as well this morning.

In terms of the latest on the AI side, there wasn’t much in the way of fresh headlines to drive markets yesterday, but we did see software and other tech stocks pare back their Monday losses. For instance, the NASDAQ (+1.04%) and the Magnificent 7 (+1.14%) both put in a decent performance, and the S&P 500’s software component (+1.28%) picked up from its 10-month low on Monday. Meanwhile, AMD (+8.77%) was the second-best performer in the S&P 500 after it was announced that Meta would acquire AMD chips with a total capacity of 6 gigawatts. So it was a strong session for tech stocks, which also supported broader US equity gains. By the close, more than 70% of the S&P 500’s companies were higher on the day, with consumer discretionary (+1.58%) and industrials (+1.23%) sectors leading the way. However, there were more concerns in the credit space, with US IG and HY spreads both edging +1bps higher, reaching their widest levels since December.

Risk assets got further support from the latest US data, as the Conference Board’s consumer confidence reading picked back up to 91.2 in February (vs. 87.1 expected). Moreover, the expectations component also rebounded to 72.0, up from a 9-month low the previous month. There were also promising signs on the labour market, as the ADP’s weekly private payrolls series hit a 2-month high, showing 4-week average growth of +12.75k in the period to February 7. So at the margins, that leant positively against the recent talk of AI-driven unemployment.

Given the more positive data and the tech stock rebound, investors also priced in a slightly more hawkish path for the Fed over the year ahead. For instance, the probability of a rate cut by the June meeting fell to just 52%, the lowest so far this year. And looking further out, just 55bps of cuts are now priced in by the December meeting, which was down -3.9bps on the day. So in turn, that pushed up front-end Treasury yields, with the 2yr yield (+2.3bps) up to 3.46%, although the 10yr yield (-0.2bps) was basically flat at 4.03%. Comments from Fed officials also leaned against imminent rate cuts, with Chicago Fed President Goolsbee warning that 3% inflation “is not good enough” and that they needed to make more progress. And Boston Fed President Collins said rate were likely to stay unchanged “for some time” and that she was looking for more confidence that disinflation resumes. There were also discussions around AI-related job losses too, with Governor Cook saying that “our normal demand-side monetary policy may not be able to ameliorate an AI-caused unemployment spell without also increasing inflationary pressure”.

Another supportive factor yesterday was the latest dip in oil prices, which helped to ease concerns on the inflation side. In part, that was driven by growing hopes for some sort of deal between the US and Iran that would avoid a military escalation. Indeed, Trump himself had posted on Monday evening after the US close that “I would rather have a Deal than not”. So that took a bit of the geopolitical risk premium out, with Brent crude down -1.01% to $70.77/bbl, whilst gold prices fell -1.60% to $5,144/oz. Trump echoed that rhetoric on a deal in last night’s State of the Union address, saying that his “preference is to solve this problem through diplomacy”.

Over in Japan, the yen weakened yesterday after the Mainichi newspaper reported that PM Takaichi was apprehensive about more rate hikes in a meeting last week with BoJ Governor Ueda. So it was down -0.78% against the US Dollar yesterday, making it the weakest-performing G10 currency. Then this morning, Japanese equities have seen a strong outperformance after the government nominated two reflationists to join the Bank of Japan’s board, who were seen as favouring more stimulus. So the Nikkei is up +2.60% this morning, on course for another record high, and bringing its 2026 gains to +16.83% already.

That optimism has been clear elsewhere in Asia, building on the overnight gains seen on Wall Street. So in South Korea, the KOSPI (+1.79%) is up for a 5th consecutive session, and also on track to close at a record. Similarly in Australia, the S&P/ASX 200 (+1.17%) is on course for an all-time high as well, despite a stronger-than-expected CPI report this morning, with inflation remaining at +3.8% in January (vs. +3.7% expected). So that’s seen investors price in more RBA rate hikes at the next few meetings, and the Australian Dollar has strengthened against every other G10 currency this morning, up +0.73% against the US Dollar. Otherwise, there’s also been gains for the Hang Seng (+0.72%), the Shanghai Comp (+0.99%) and the CSI 300 (+0.86%).

Earlier in Europe, most assets had also put in a decent performance yesterday, with the STOXX 600 (+0.23%) paring back some of Monday’s losses as well. That came as longer-dated yields continued to fall across the continent, with yields on 10yr gilts (-0.9bps) and BTPs (-0.5bps) at their lowest since December 2024, whilst 10yr OAT yields (-0.8bps) reached their lowest since July. For 10yr bund yields (-0.4bps) there was a comparatively smaller fall, but yields still closed at their lowest since November.

Looking at the day ahead, one of the main highlights will be Nvidia’s earnings after the US close tonight. Otherwise, central bank speakers include the Fed’s Barkin, Schmid and Musalem, and the ECB’s Vujcic. There’s not much data, but we will get the final Euro Area CPI print for January, along with the final Q4 GDP release from Germany.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 02/25/2026 - 08:33

Virginia Gov. Abigail Spanberger delivers the Democratic response to President Donald Trump’s State of the Union address in Williamsburg, Va., on Feb. 24, 2026. Mike Kropf/Getty Images

Virginia Gov. Abigail Spanberger delivers the Democratic response to President Donald Trump’s State of the Union address in Williamsburg, Va., on Feb. 24, 2026. Mike Kropf/Getty Images

Recent comments