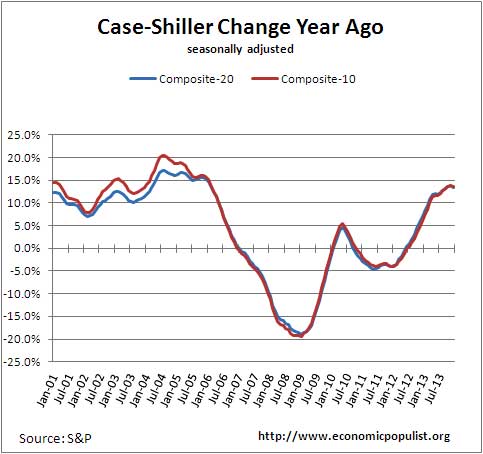

The December 2013 S&P Case Shiller home price index shows a seasonally adjusted 13.4% price increase from a year ago for the 20 metropolitan housing markets and a 13.6% yearly price increase in the top 10 housing markets. While just slightly lower than last month's year ago price increase, the yearly price jumps are still in line with the February 2006 housing bubble. The two indexes are comparable to July 2004 price levels and 2013 is the highest price increase year since 2005. S&P claims the party is over and momentum is slowing, yet prices are now only 20% away from their peak over-inflated housing bubble years price levels.

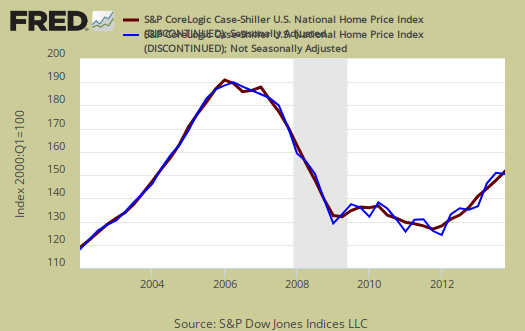

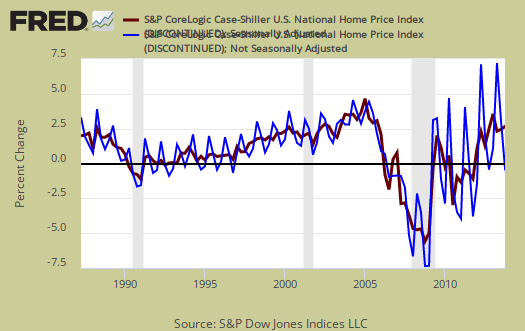

S&P also produces a third quarterly national index. S&P is using the not seasonally adjusted national index when they report Q4 2013 home values are down -0.3% from Q3 2013, although the seasonally adjusted change is 2.6% between quarters. Below is the national index, not seasonally adjusted (blue), which are used as the headline numbers, against the seasonally adjusted one (maroon). We believe the seasonally adjusted 2.6% quarterly change is more accurate, due to the seasonality of the real estate market.

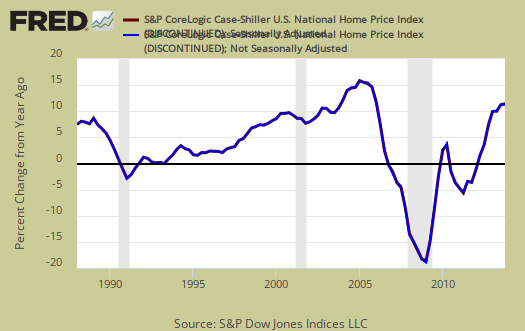

Below is the quarterly national index percent change from a year ago, now at 11.3%. The national index also shows soaring prices and the lack of affordable housing as a major reason prices might have plateaued.

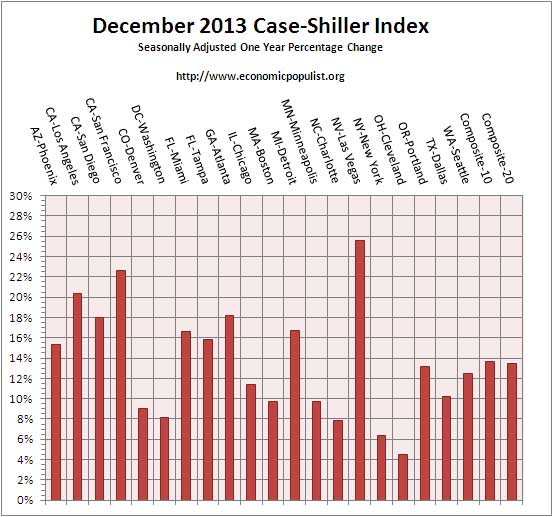

Below are all of the composite-20 index cities yearly price percentage change, using the seasonally adjusted data. Las Vegas appears to be a re-bubbling cauldron and San Francisco is now the site of protests for affordable housing. Generally speaking the West is clearly not affordable for most people. Either investors are purchasing these homes or something has to be returning to financial bubble like state, for the localized median income comes nowhere near being able to afford a mortgage at these prices. Since March 2012, prices have increased 23-24% for the 10 and 20 city composite indexes.

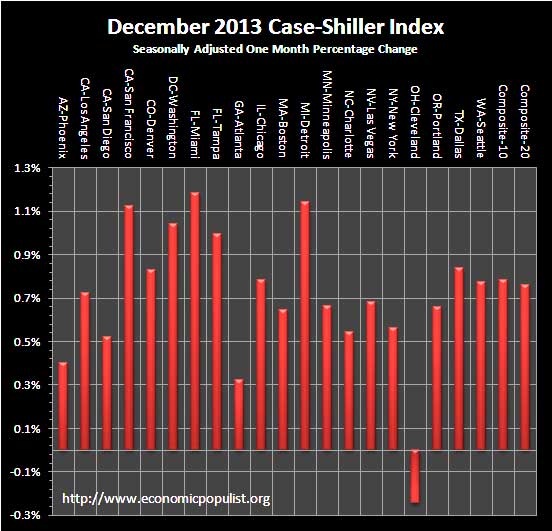

S&P reports the not seasonally adjusted data for their headlines. Housing is highly cyclical. Spring and early Summer are when most sales occur. See the bottom of this article for their reasoning. For the month, the not seasonally adjusted composite-20 percentage change was -0.1% whereas the seasonally adjusted change for the composite-20 was 0.8%. The not seasonally adjusted composite-10 saw no change from last month, whereas the seasonally adjusted composite-10 showed a 0.8% increase. This is winter and a very harsh winter at that, so the not seasonally adjusted increase should be less than the seasonally adjusted composite-20. The below graph shows the seasonally adjusted monthly percentage change.

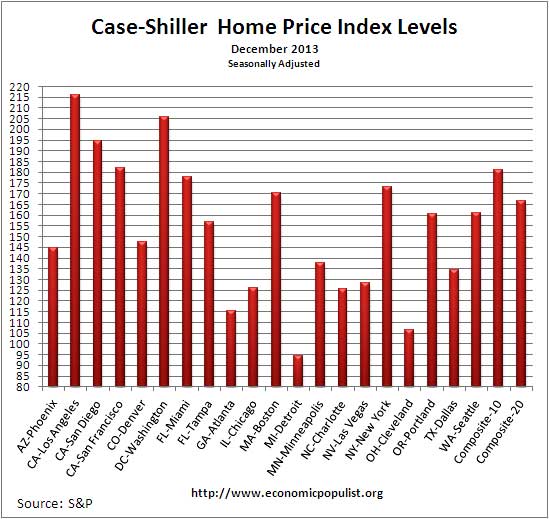

Prices are normalized to the year 2000. The index value of 150 means single family housing prices have appreciated, or increased 50% since 2000 in that particular region. Case-Shiller indices are not adjusted for inflation. Below are the seasonally adjusted levels for the month.

Bottom line home prices eventually must level off. There are many other housing indicators showing this is the case. While investors probably made out like bandits, prices are clearly out of reach for most first time home buyers. Only when incomes come into alignment with home prices will we feel the residential real estate market is healthy and sustainable.

To Season or Not to Season, That is the Question:

The S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices are calculated monthly using a three-month moving average and published with a two month lag. Their seasonal adjustment calculation is the standard used for all seasonal adjustments, the X-12 ARIMA, maintained by the Census.

So, why would S&P report the not seasonally adjusted data? According to their paper on seasonal adjustments, they claim the not seasonally adjusted indices are more accurate. It appears the housing bubble burst screwed up the cyclical seasonal pattern. What a surprise, although those steep cliff dives are now going back to 2009, one would think the seasonally adjusted data would now start to converge back to it's cyclical, seasonal pattern.

The turmoil in the housing market in the last few years has generated unusual movements that are easily mistaken for shifts in the normal seasonal patterns, resulting in larger seasonal adjustments and misleading results.

To see S&P's argument in action, look at the below graph. The maroon line is the seasonally adjusted national index, reported quarterly. The blue line is the not seasonally adjusted national index. As we can see before the housing bubble burst, we see a typical cyclical pattern difference between the seasonally adjusted and not seasonally adjusted data points. Yet after the bubble burst we see large swings, which would throw off a seasonal adjustment adaptive algorithm. This is going to become a major question among statisticians, how does one adjust for seasonality in the face of tsunami like economic events? Is it now long past the housing bubble collapse, yet we can see the seasonal adjustments still are not completely matching up from the year ago percent changes, which implies they are still off statistically.

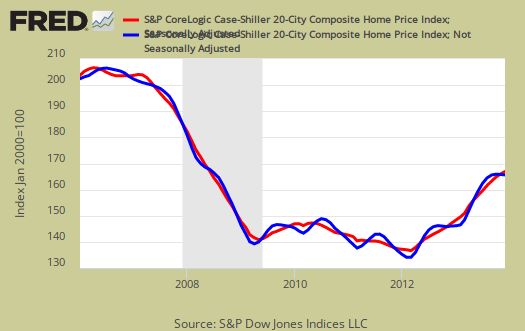

Not seasonally adjusted data can create more headline buzz on a month by month basis due to the seasonality of the housing market. S&P does make it clear that data should be compared to a year ago, to remove seasonal patterns, yet claims monthly percentage changes should use not seasonally adjusted indices and data. This seems more invalid than dealing with the statistical anomalies the massive housing bubble burst caused. Below is the seasonally adjusted and not seasonally adjusted Composite-20 Case-Shiller monthly index, for comparison's sake.

For more Information:

S&P does a great job of making the Case-Shiller data and details available for further information and analysis on their website.

Here is our Case-Shiller past overviews as well as the overviews of residential real estate statistics.

Recent comments